Capital Punishment and Christian Soteriology: The Historical Relationship Between the Death Penalty and Christian Understandings of Christ's Salvation

The history of the Western world is one tainted by the ever-presumed existence of violence. From the ancient conquests of fourth-century Hellenism to the twentieth-century development of nuclear warheads, violence has been endemic in the existence of the Western world. This violence has existed perpetually in a variety of forms, from horizontal chaos and relational violence to the state-executed killing of condemned individuals. However, the latter is endemic to the West in a specific way – it lies at the center of its central religion. In this ethical study, I will explore the relationship between the religion of Christianity and the existence of state-mandated capital punishment. Specifically, I will engage in careful study of conceptions/depictions of salvation in both (1) capital punishment at the behest of the state and (2) historical soteriological understandings of the death of Jesus Christ. Through this, I aim to demonstrate the inextricable relationship that exists between the two, and further, I assert that they have reciprocally and perpetually influenced each other throughout the last two millennia.[1]

In investigating the nature of capital punishment within the pre-Constantinian Roman Empire, one of the most-available sources in the Christian Scriptures. Throughout the New Testament, there are various depictions/descriptions of capital punishment at the behest of Rome. In the New Testament, the following modes of capital punishment are referenced: (1) crucifixion, (2) beheading, and (3) stoning, with the foremost depiction at the forefront of our discussion in the crucifixion of Jesus Christ.[2] However, what is significant to this ethical study are not the modes of execution utilized, but rather, it is the context within which the two most prominent New Testament executions were sanctioned.[3] Both the executions of Jesus Christ and John the Baptist were “killing[s] initiated and carried out by the [occupying] government” of Judea: Rome.[4] Rome was not chosen to rule Judea by Judeans, but rather, Rome forcefully conquered Judea in the 1st century BCE.[5] This manner of capital punishment, therefore, was neither sanctioned nor chosen by the Judeans whom it bound.[6]

Out of the aforementioned Roman executions came an understanding of capital punishment as a tool of imperial domination, and out of the execution of Jesus Christ came a religious understanding of salvation. The religion of Christianity was founded upon the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and it claimed that salvation could be found for all through Jesus (the) Christ.[7] But by what mechanism was this salvation able to be received? In what way did the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ bring salvation to all of those who sought it? In respect to these questions, one consequential theory of atonement was developed by Origen of Alexandria in the pre-Constantinian Roman Empire: Ransom Theory.[8]

In the 3rd century CE, Origen posited the Ransom Theory of Atonement, which states that “Christ’s death on the cross was a price paid [to Satan] to satisfy the debt humanity owed due to Adam’s Fall.”[9] This theory advocated that Jesus Christ’s death brought about salvation through the paying of a debt to Satan. One key aspect of this theory of atonement is key to understanding the correlation between Roman capital punishment and the theory's conclusions: its assertion that humanity’s debt was paid to Satan. Under the imperial occupation of Rome, early Christians (who were still very connected to Judaism and Judea) saw that Jesus Christ was killed by Romans, and they viewed his killing as unjustly committed by occupying powers. In Rome’s execution of Jesus Christ, early Christians likened Rome to Satan, and therefore, they saw Christ’s death as a payment to Satan for reconciliation. This theory of atonement was the product of an occupied people who were subject to unjust execution by imperial powers.

In the fourth century, Emperor Constantine of Rome converted to Christianity, and consequently, Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire.[10] The nature, culture, and demographics of Christianity changed over the next several centuries, with Christianity eventually becoming the dominant religion across the European Continent. The Empire of Rome ultimately fell, but its religious, social, and political influence was foundational for the Western world in the Middle Ages.[11] During this period, capital punishment changed greatly, shifting both in method and nature. There was a great “Christianization of death as punishment” during this period, uniting the capital punishment of the state with the established religion of Christianity.[12] This resulted from Christianity’s “reached agreements and compromises with laws, customs, forces, and traditions of every kind” that permitted execution for the retention of power.[13] This ultimately led Christianity in the Middle Ages to effectively justify the death penalty as a legal and religious practice.

As the religion of Christianity merged with the various political states of Medieval Europe, so did the theories of atonement that it espoused. No longer oppressed under imperial power, Christianity transformed into the prevailing socio-religious system of this new era of Western society, and with that, Christianity’s atonement theories became congruent with the socio-cultural power that Christianity had obtained. This is best exemplified in the Satisfaction Theory of Atonement.

Espoused by Anselm of Canterbury in the 11th century, the Satisfaction Theory of Atonement claimed that “Jesus’s innocent death on behalf of sinful human beings presented something to God as atonement for human sin [and] satisfied God’s just requirement of judgment in response to sin.”[14] In contrast to the Ransom Theory, the Satisfaction Theory posited God as the one who “received payment” upon Christ’s death. Though not as explicitly economic, this theory of atonement still espouses exchange, primarily in terms of justice. This medieval theory of atonement claims that Jesus’s death was a full payment pertaining to the requirement of justice. Therefore, I assert that this theory's God can be likened to the governments of the Middle-Age European states. Just as God necessitated the state-sanctioned execution of Jesus Christ in the Satisfaction Theory, so too did Middle-Age governments necessitate capital punishment as a method of maintaining societal order in their feudal states and “empires.”

The transition from Medieval to Modern-Era Europe was a complex process that took place over many years, with the core transition taking place from the 15th to 16th century. During this time, two key socioreligious developments took place, transforming both the nature of society and the place of Christianity as Western society’s de-facto religion. These developments were (1) the Renaissance and (2) the Protestant Reformation. Originating in Italy, the Renaissance was a movement that emphasized humanism, led to a resurgence of interest in literature and the arts, and aspired to the ideals of the Greek and Roman civilizations.[15] The Protestant Reformation was a movement that began in the 16th century by Martin Luther that attempted to reform the Roman Catholic Church. Ultimately, it led to economic, political, religious, and societal upheaval, resulting in multiple new versions/denominations of Christianity and large shifts in the political realm of Europe.[16] The largest shift in the political realm during this era was the establishment of republican governments, in contrast to the Middle-Age system of feudalism.[17] Further, it is also important to note that the Reformation brought about many new theological ideas and systematizations, such as those in John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion (1559).

Amid these vast changes, there was also a great shift in how capital punishment was mandated in the Western world. Capital punishment went from being a power-maintaining action of "Christian" Middle-Age feudalism to being used in many ways that both maintained and disrupted order across Western society. Two primary examples that demonstrate this variance are (1) John Calvin’s Geneva and (2) Revolutionary France. In the former, a religious utilization of capital punishment was maintained and purported through the state religion of Calvinism, in contrast to the Catholicism of Middle-Age Europe. Changing European religious ideals, due to the Reformation, allowed this city-state to exist and utilize capital punishment in this way. In the latter, capital punishment was used by the masses as a means for secular, republican revolt against the monarchy of the French Empire. This secular, "mass-controlled" execution heavily contrasts with the socio-religious executions of Middle-Age Europe.

Amidst the shifts from (1) feudalism to republicanism and (2) Catholic to Protestant theologies, there was yet another shift/development in Christian theories of atonement. During this time, multiple new theories of atonement were posited, and the foremost of these was the Penal-Substitution Theory of Atonement. This theory of atonement asserts that “Jesus substituted his life for [the lives of humanity] so that [humans] need not die [an] eternal death in hell for [their sins].”[18] This theory lies on its foundational belief that humans have “kindled God’s wrath against [humanity]” and therefore are deserving of punishment.[19] Though having roots in the aforementioned Satisfaction Theory, the Penal-Substitution Theory of Atonement advocates that God is wrathful against humanity, necessitating satisfactory punishment. This rather novel and cruel portrayal of God is consistent with the theological renderings of Martin Luther and John Calvin, the latter of whom espoused this theory.[20] Just as there was an ideological explosion from the Middle Ages to the Modern Era, so too was there an ideological explosion in the realm of Christian theology. Further, as there was a move from Catholic feudal states to secularized Protestant states, the nature of capital punishment shifted from one of entwined religious and political purposes to one of great purposeful variety. During this period, Christian theories of atonement reflected the world around them, changing and growing in a plethora of previously unheard-of ways – parallel to the new modes and purposes of capital punishment across the changing landscape of Western civilization.

Since the Modern Era, the world has expanded and changed in ways considerably more-rapid than those in previous eras of Western Civilization. Of these developments, the (arguably) most-consequential was the European colonization and Westernization of the Americas.[21] Within this colonization, there was a mass, multifaceted exchange between the “Old World” and the Americas, dubbed the “Colombian Exchange.” This exchange promulgated an egregious societal sin, around which this discussion of capital punishment in contemporary empire is situated: the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

Within the Transatlantic Slave Trade, many thousands of black Africans were kidnapped from their homes and made slaves within the racially domineered and oppressive system of chattel slavery. A system fueled by the aforementioned slave trade, this system uplifted the “white man” and viewed black people as “inhuman.” This system allowed and purported the thorough brutalization of black people, with violence (of all repulsive types) constantly being committed against them – culminating in a culture of murder that targeted black people above all races. The state-allowed and state-sponsored execution of runaway slaves became the new nature of capital punishment, taking upon a form increasingly distanced from its prior iterations. This ultimately progressed to encompass the post-Civil War and Jim Crow lynchings of black people, the continual disproportionate murder of black people by police, and the continued inequitable amount of state executions of black people in the United States legal system.[22] Due to this historical and continued involvement of the state in these continually unjustified executions, I assert that this disproportionate killing of black people serves as the nature and form of capital punishment amidst contemporary empire.

This transformation of capital punishment in the late-modern and contemporary Western world has been integral to the changing nature of Christianity. Amid this vast “expansion of the world” and the adaption of racially domineered societal systems of oppression, a plethora of new theological understandings have arisen, such as various types of liberation theologies and restorationist movements. Amidst this, one key revolutionary theory of atonement holds great implications and promise for those who are oppressed under the current system of racially charged capital punishment: the Scapegoat Theory of Atonement. Proposed by René Girard in his monograph The Scapegoat (1986), the Scapegoat Theory asserts that humans, motivated by memetic desire, will become rivals of one another and covet their possessions, thereby threatening societal breakdown.[23] In order to avoid this breakdown, society will choose a “scapegoat” to kill, thereby releasing rivalries and restoring peace. The theory claims that the Bible, which unveils the aforementioned process, claims that truth is on the side of the oppressed (the scapegoat) not the oppressors. Further, the theory notes that this “unveiling has acted as a slow but steady yeast, working its way into Western culture for three millennia.”[24] In describing this theory's relation to Jesus Christ and his execution, Girard states that “the Gospels reveal the scapegoat mechanism everywhere,” and he asserts that Jesus Christ holds the identity of a scapegoat.[25] Further, he ultimately states the following: “all violence will reveal what Christ’s passion revealed, the foolish genesis of bloodstained idols and the false gods of religion, politics, and ideologies... [the] time has come for [humans] to forgive one another.”[26] This theory of atonement can be applied greatly to the aforementioned plight of black people in the United States, wherein it is they who have perpetually been scapegoated by white scapegoaters.[27] As Western society transitioned to a world that heavily employed (and still employs) racially domineering systems of societal oppression, theories of Christian atonement developed and reacted in parallel ways.[28] As people of minority communities have been continually killed and murdered within racially-motivated state systems across Western society, theories of liberative atonement, such as the Scapegoat Theory, have been developed to combat this contemporary and racialized form of capital punishment.

-----

Postscript: A Desire to Pursue Further Research

-----

As I engaged in research for this study, I encountered a plethora of historical Christian theories of atonement beyond those that I presented in this study. From early Christianity to the contemporary era, various Christian theories of atonement seem to have also transformed alongside and been influenced by historical renderings of capital punishment. Limited by space, I was not able to incorporate all of these theories into my study. These notable, unmentioned theories include the following: (1) Christus Victor Theory, (2) Recapitulation Theory, (3) Christian Universalist Theory, and (4) Governmental Theory. I believe each of these theories to hold great potential concerning this topic and would be of great benefit in an expanded study.

I also desire to provide more-specific links between historical developments and the Christian atonement theories. I believe these connections to be much richer than I was able to convey in the short length of this report. I also posit that there is great potential in studying the level of acceptance that each theory received in both (1) its own time and (2) the time following its development. I look forward to continuing to research the relationship between Western societal development and Christian theories of atonement, as I believe the implications of this study to be deeply significant for both (1) the theological study of Christian atonement and (2) the ethical study of capital punishment within contemporary empire.

-----

Notes

-----

[1] In this paper, I explore this inextricable ethical relationship, but I do not cite many specific instances in which they have claimed to influence each other. Rather, I explore/investigate the co-development of the themes that underlie each of the two.

[2] Gardner C. Hanks, Capital Punishment and the Bible (Scottdale, PA: Herald Press, 2002), 161, 174, 179.

[3] I have chosen to omit discussion concerning Stephen’s stoning in Acts 7, as this execution was not state-sanctioned and is therefore not comparatively integral to this ethical study.

[4] Hanks, 161; I acknowledge that John the Baptist’s execution was ordered by King Herod. However, I am choosing to view Herod as a king with dual allegiance to Rome (first) and Judea (second).

[5] Matthias Henze, Mind the Gap: How the Jewish Writings between the Old and New Testament Help Us Understand Jesus (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2017), 24.

[6] This is not to assert that Judeans did not attempt to mandate or sanction capital punishment. In this sentence, I am solely referencing Roman executions, which heavily influenced Judean citizens.

[7] It is debated whether Christianity was considered an individual religion prior to the conversion of Emperor Constantine in the early 4th century. Though I note it as a religion for the purposes of this paper, I acknowledge that it may have been a sect during this time.

[8] In this study, I have chosen to only focus on one theory of atonement per allotted time period. This was done primarily for length. I believe other theories provide further insight concerning my central claim, as is stated in my postscript.

[9] Isaac Boaheng, “A Theological Appraisal of the Recapitulation and Ransom Theories of Atonement,” E- Journal of Religious and Theological Studies 8, no. 4 (April 8, 2022): 98–108, https://doi.org/10.38159/erats.2022841, 103; Paul P. Enns, The Moody Handbook of Theology: Revised and Expanded (Chicago: Moody Publishers, 2014), 331.

[10] Adele Reinhartz, “Jesus, Paul, and the Founding of Christianity,” Lecture on Zoom, (April 15, 2024).

[11] This is an extremely brief overview of Christianity’s progression from a small sect to the primary religion of Europe. With more space, I would aim to expand my explanation of this history of expansion.

[12] Adriano Prosperi, Crime and Forgiveness: Christianizing Execution in Medieval Europe, trans. Jeremy Carden (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020), xii.

[13] Ibid.

[14] James David Meyer, “The Patristic Roots of Satisfaction Atonement Theories: Did the Church Fathers Affirm Only Christus Victor?,” Tyndale Bulletin 71, no. 2 (2020): 293–319, 293-294.

[15] Jean Reeder Smith and Lacey Baldwin Smith, Essentials of World History, Revised (Hauppauge, NY: Barron’s Educational Series, Inc., 1980), 77.

[16] Smith and Smith, 78-81; This is a very simplified version of the Reformation. With more space, I would aim to expand my explanation of Reformation history, specifically including reformers and reform movements.

[17] Many republican governments, such as that instituted in Switzerland by John Calvin, failed to be true republics. However, the conceptual idea of republicanism and its introduction into the mainstream is historically significant, in general and for the purposes of this study.

[18] Kevin D. Kennedy, “Revisiting Penal Substitution,” Journal for Baptist Theology and Ministry 2, no. 2 (2004): 38–54, 38.

[19] Ibid, 38-39.

[20] Timothy Gorringe, God’s Just Vengeance: Crime, Violence, and the Rhetoric of Salvation (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 25.

[21] Though this happened in the waning years of the Modern Era, this development was instrumental in my discussion of the Scapegoat Theory and capital punishment in contemporary empire. Further, this development is consequential to the development of Western society and the Christian religion.

[22] Charles K. Bellinger, The Tree of Good and Evil: Or, Violence by the Law and against the Law (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2023), 10; Michael Fraser, “Crime for Crime: Racism and the Death Penalty in the American South,” Social Sciences Journal (Western Connecticut State University) 10, no. 1 (2010): 20–24, 22.

[23] Bellinger, 4; I further utilize this source in the subsequent sentences.

[24] Ibid.

[25] René Girard, The Scapegoat, trans. Yvonne Freccero (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 100.

[26] Ibid, 212.

[27] Bellinger, 56.

[28] I recognize that Girard’s Scapegoat Theory was likely not influenced directly by the societal oppression of black Americans, but I do assert that contemporary empire’s utilization of these systems (along with past iterations of such) likely influenced him in some capacity.

-----

[Photo #1] Photograph of a relief of Roman soldiers. Photo pulled from the following webpage: Mark Lamas Jr., “‘Roman’ Soldiers in Pre-War Palestine? The Local Supply of Soldiers in New Testament Times,” Urbs and Polis, October 11, 2021, https://urbsandpolis.com/roman-soldiers-in-pre-war-palestine/.

[Photo #2] Painting of Alfonso X of Castile from the Libro des Juegas. Photo pulled from the following webpage: DUCKSTERS, “Middle Ages for Kids: Kings and Court,” Ducksters.com, 2018, https://www.ducksters.com/history/middle_ages/kings_and_court.php.

[Photo #3] Painting of John Calvin and others in Geneva. Photo pulled from the following webpage: W. J. Grier, “John Calvin’s Geneva,” www.monergism.com, n.d., https://www.monergism.com/john-calvins-geneva.

[Photo #4] Howard Brodie’s “Capital Punishment, Lawyer Anthony Amsterdam Arguing” from May 4, 1970. Photo pulled from the following webpage: “Death Penalty Argued before the Supreme Court | Significant and Landmark Cases | Explore | Drawing Justice: The Art of Courtroom Illustration | Exhibitions at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress,” Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, n.d., https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/drawing-justice-courtroom-illustrations/about-this-exhibition/significant-and-landmark-cases/death-penalty-argued-before-the-supreme-court/.

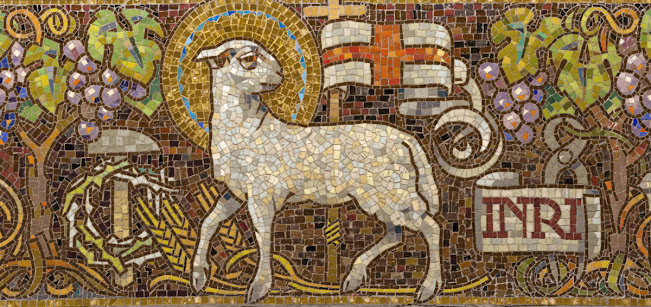

[Photo #5] Photograph of mosaic with Lamb at the center. Photo pulled from the following webpage: Peter Watts, “7 Atonement Theories from Church History,” Faith Rethink | Following Jesus Today, June 13, 2022, https://faithrethink.com/7-atonement-theories-from-church-history/.

-----